Climate Change: Banks and Insurers in the Crosshairs

By Ashutosh Singh and Jaishree Singh

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2019) has said that, “Based on current policies and commitments, global emissions are not estimated to peak by 2030 – let alone 2020.” (Boston Common, 2019) says “[t]hat time for incremental change is over. We need to see transformation in the banking sector and the adoption of system-level thinking.” Central banks and regulators are exploring mandatory climate risk disclosures and climate stress testing, while the Network for Greening of Financial System (NGFS) supports integrating climate risk into financial stability monitoring and supervision.

The Adaptation Commission of the World Resources Institute (Bapna, et al., 2019) is calling for a “revolution in understanding, planning, and financing that makes climate risk visible.” The banking and insurance industries have an important role to play, as well as in supporting innovation to assist in the low-carbon transition. The banks can reduce their exposure to the fossil fuel industry in their lending and investing portfolios. They have collectively provided financing to the tune of almost $2 trillion for dirty fuels since the Paris Accord came into effect – an amount that far exceeds their sustainable finance commitments during the same period. (Boston Common, 2019).

This literature review concludes that if the world is to contain the pernicious effect of climate change then,

- Governments and regulators will need to create mechanisms for carbon pricing, renewable energy mandates, electric vehicle support, and tax subsidies and/or penalties

- Regulators will need to ask for greater transparency and disclosures on scopes 1, 2 and 3 emissions from the corporations. They will also need to create clear guidelines to measure and report these metrics.

- Banks and insurers will play a pivotal role in financing projects, investing in companies, and underwriting risk.

- Banks and insurers will need to treat climate risk as a financial risk and integrate climate considerations into their financial risk management frameworks

- Banks and insurers can take advantage of considerable opportunities in the evolving trends energy, mobility, and underwriting of risk. They will also reduce their market, credit, reputation, regulatory and legal risks. And, they can advise their clients to best manage their exposure to the climate transition and physical risks thereby reducing their risks.

- All entities – corporations, state and local governments, financiers, insurers and asset managers – will need tools and data to assess and manage risks. This creates an opportunity for data providers and analytics firms who can assess the impact of climate risk factors with financial and operating factors such as revenue growth and cash flow.

Introduction

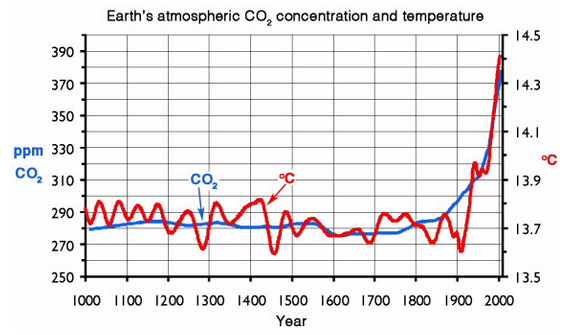

It’s true that the climate has changed before many times during the earth’s history based on the contents of the ice cores that were drilled from the deep ice sheets in Antarctica and Greenland. However, as Figure 1 shows – the pace of the increase and the rise in level in CO2 concentration and temperature have been dramatic (Dlugolecki and Lafled, 2005) (NOAA, 2020). The impact of the increase in temperature is being felt in melting glaciers and polar ice caps, extreme weather events and rise in sea levels. A Boston Consulting Group (BCG) survey of 3,000 people in eight countries, found that 70% of the people are now more aware (than pre-COVID-19) that human activity threatens the climate (Waddell and Beal, 2020).

Figure 1: Earth’s atmosphere CO2 concentration and temperature (courtesy Hanno, Wikimedia Commons)

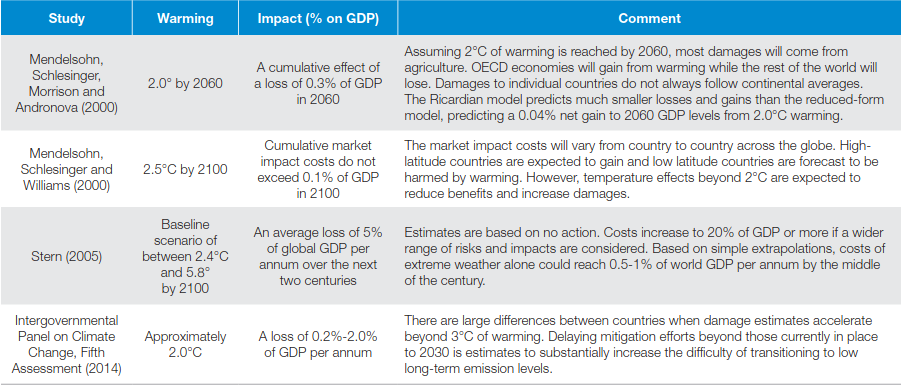

Climate change poses a significant risk to the global economy: It affects the wealth of societies, the availability of resources, the price of energy, and the value of the companies. (Steele and Faber, 2005). (Wade and Jennings)’s summary of losses range in Figure 2 vary mainly because of inherent uncertainties related to climate change and the society and businesses’ response. The (Stern 2005/2006) and (Steele and Faber, 2005) reports shows that developing countries who are largely in tropical climates are most likely to bear the brunt of climate-related events (as shown in Figure 3). However, the frequency and ferocity of hurricanes, floods, and wildfires in the U.S, Europe, and Australia show that losses could become expensive even for rich countries. (Waddell and Beal, 2020).

Figure 2: Estimates of Economic Losses from Climate Change (Courtesy: Schroders)

Figure 3: Macro-economic Effect of Climate Change (Courtesy: IPCC, 2001)

Climate Change – A Challenge for Banks & Insurers

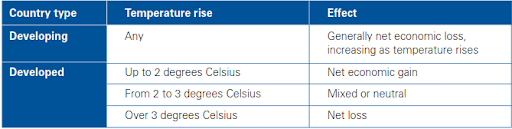

The present day climate crisis is becoming an important factor for the financial sector in its insurance, banking and investment activities. Thus far the financial sector has been involved in the management of climate variability through its provision of credit for seasonal cycles of agriculture, selection of investment opportunities, and insurance against natural disasters, and has gained an invaluable amount of experience in that area. However now, change is not only definite but accelerating. The risks faced by the financial sector and its clients will be different, and distributions of the returns of the current and future investments will change from the customary ones. These risks will emanate from number of directions – physical changes in the environment (crop yields in the tropics, water supply and sea levels), regulatory moves to limit greenhouse gases (GHG) emissions, legal challenges to inadequate governance, reputational fallout from the corporate position on climate change, and competitive pressures as production costs shifts and products are substituted in response to new economics of a low-carbon world. Climate risks are broadly classified in physical and transition risks as Figure 4 shows.

Figure 4: Physical Risk and Transition Risks (Courtesy: RBCCM)

(CFTC, 2020) says to adequately address the question of physical and transition risks to financial institutions, one must ask:

- Which combinations of assets could be affected by climate-related (CR) risks? By how much, and how quickly?

- Who holds those assets and what is their ability to absorb the losses?

- To what extent are losses mitigated by public and private shock absorbers?

We answer these questions in the context of risks such as: credit, operational, market and liquidity, and regulatory and legal.

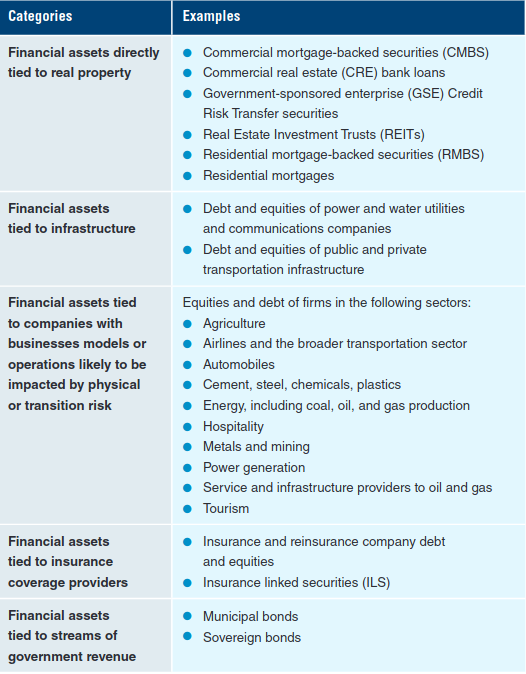

Assets affected by climate-related risks

The assets most likely to be impacted by climate-related risks are tied to:

- Real property

- Infrastructure

- Companies whose business is affected by climate related risks

- Coverage providers (namely insurers and reinsurers)

- Government revenue

Consider the impact of major flooding (an example of physical risk) of residential and commercial property over a large region in a short time. This could result in rise in mortgage delinquency and prepayment rates and falling values of residential MBS, securitized commercial real-estate (CRE) loans, the bonds of affected municipalities, and the stock of insurance companies (if they must make large payouts for flooded commercial property).

In the context of transition risk, consider sudden adoption of ambitious climate policy or a sudden shift in perceptions about the likelihood of a major policy change (as a result of elections) – aimed at limiting GHG emissions. Even if the policy is phased in gradually the mere adoption or a perception could affect the equity and stock values, investment, and payroll of companies across several sectors, assuming that the costs of compliance are not fully passed on to the customers. Aside from the fossil fuel industry, auto and auto-parts, and transportation and warehousing could be impacted. (Jorgenson, et al, 2018). Figure 5 summarizes categories of assets exposed to climate risks.

Figure 5: Categories of Assets Exposed to Climate Change Impacts (Courtesy: CFTC, 2020)

Who holds these assets, and what is their ability to absorb the losses?

The degree to which climate risks become material for specific banks and other firms will depend on those institutions’ capability to measure and manage those risks.

Lending institutions. Commercial banks and other credit providing institutions lend to entities in locations and sectors that may experience climate-related impacts. Banks could both suffer losses from impaired loans and be left less able to to provide credit to affected entities or even entire sectors. Banks who lend to carbon-intensive industries may have some time to course-correct when facing policy or technological change that increases the price of carbon and limits their clients financial prospects. Partially, this is because the loans are for 1-3 years which gives banks time to modify the terms and conditions and incorporate newly identified credit risks. In the long-term, however, risks for banks would grow if they stopped lending to carbon-intensive industries without replacing those assets with companies that are better able to adapt to higher carbon asset risk. Certain policy paths or the perception about the likelihood of a shift in policy could trigger an abrupt downturn in revenues and valuations for companies in carbon-intensive sectors, possibly forcing the banks to recognize credit losses on their loans and mark-to-market losses on their securities holdings.

The largest US banks are relatively well positioned to cope with sudden climate-related extreme events, such as storms, floods and wildfires because their portfolios are typically geographically and sectorally diversified. (Landon, et al. 2011) find that bigger banks may be better able to offset temporary regional losses from natural disasters with earnings from other regions. Large banks are also more resilient to particular climate-related extreme events than smaller rivals because they have more diversified business models and are required by regulators to hold more capital relative to their assets.

(UNEP FI, 2017) In 2017 nine major US banks voluntarily conducted a scenario analysis of how water stress might affect creditworthiness among a sample of their borrowers. It showed that extreme droughts could increase default tenfold for certain bank portfolios. The most affected sectors were water supply, agriculture, and in certain countries, power generation. In several cases, most of the financial losses came from slow-onset, chronic impacts such as drought, not from sudden extreme events. The key question for large banks remains not only how to manage these longer-term physical risks but also how to manage them in context of potentially growing transition risks.

Regional and community banks are comparatively more vulnerable to regionally concentrated physical risk, including sudden extreme events. In 2019, community banks held 30% of all commercial real-estate (CRE) loans worth about $700 bn. These banks’ property loans tend to be geographically concentrated than the loans of larger banks, and CRE loans constitute a much larger share (a 33%) of the loan books of the small banks (compared to 5% for the larger banks).

Similarly, small banks in the Midwest, in particular, hold proportionally more of certain types of agriculture loans that could be affected by climate impacts. Flooding and extreme heat reduce crop yields and disrupt agriculture production. In the spring of 2019, bankers lending in the Midwest reported to the Chicago Fed that estimated 70% of the borrowers were at least moderately affected by extreme weather events in the first half of the year.

Institutions holding climate impacted assets

Banks, pension funds, endowments, mutual funds, and insurance companies operate along a wide spectrum of investment horizons and risk appetites. Many of them hold assets that may be affected by physical and transition risks. Ineffective management of these risks could lead to large financial losses which in turn could trigger asset fire sales and elevated counterparty risk. These events can channel financial contagion. Also, as climate risk is expected to increase over time, asset holders with longer asset-liability structures are more exposed to climate risk. (CFTC, 2020)

To what extent are losses mitigated by public and private shock absorbers?

Whether and how financial institutions incur destabilizing losses because of climate risks depends largely on the presence of shock absorbers, namely private insurance and reinsurance. In addition, government assistance to people and businesses during extreme events plays a crucial role in directly mitigating risks for those who are impacted and indirectly in terms of how risks are transmitted across the financial system. The limitation of the government financial shock absorbers will be an especially pressing issue in the face of enormous fiscal burdens from the COVID-19 crisis all over the world. If investors lost confidence that public and private shock absorbers would continue absorbing climate-related losses to the extent they have, fear in financial markets could trigger a disorderly adjustment of prices in one or more asset classes. (CFTC, 2020)

Often insurers and reinsurers raise premiums in the wake of the disasters to replenish their capital buffers. If they cannot (because state regulators impose limits on such increases), they may decide to exit that market altogether. For example, home insurers left the home flood insurance market decades ago.

Systemic Risks

Systemic risks can also play a disruptive role in the financial markets when the market participants have not priced those risks. (Adrian, et al., 2014) state that systemic shocks have the following characteristics:

- Shock amplification – conditions in the financial system that allow a given shock to propagate widely, magnifying its disruptive effect

- Disruption or impairment of all or part of the financial system meaning that portions of the system cease to effectively support the economic activity

- Severe externalities, meaning spillover affect the real (non-financial) economy

Climate change risks fit this characterization. Standard asset pricing theory suggests that market participants will demand a premium to hold assets exposed to physical and transition risk. When those risks are not fully reflected in the prices, market participants will accumulate large exposures to risky assets than would otherwise be desirable. A sudden revision of market participants’ perceptions about climate risk could trigger a disorderly repricing of assets, which could have cascading effects on portfolios and balance sheets and therefore systemic implications for financial stability (CFTC, 2020).

Furthermore, the fact that climate-related risks do not operate in isolation makes a systemic shock more likely. Transition and physical risks could interact and compound the disruption either would exert on its own. Additionally, at least in the short to medium term, the financial institutions’ balance sheets are stressed as a result of COVID-19, household wealth is depleted, and businesses and govts have borrowed heavily to support their respective economies. Climate-related shocks can magnify any of these already serious vulnerabilities, increasing the probability of an overall shock with systemic implications. (CFTC, 2020)

The physical and transition risks will likely introduce systemic and new strategic risks associated with the challenges and opportunities of sectoral reallocations of economic activity, new production patterns, and evolving industry exposures.

What could trigger repricing?

- Election outcomes

- Reports of technological breakthroughs that reduce the cost of zero-carbon tech

- New research findings about the speed and nature of physical climate impacts and the occurrence of major catastrophes that raise awareness of new risks

The financial sector needs to evolve its products, services, internal processes, and policies such as risk management to meet the challenges its clients face as well as ensure its own viability. We look at two industries – banks and insurance – and examine their respective risks and opportunities from climate change.

Banks

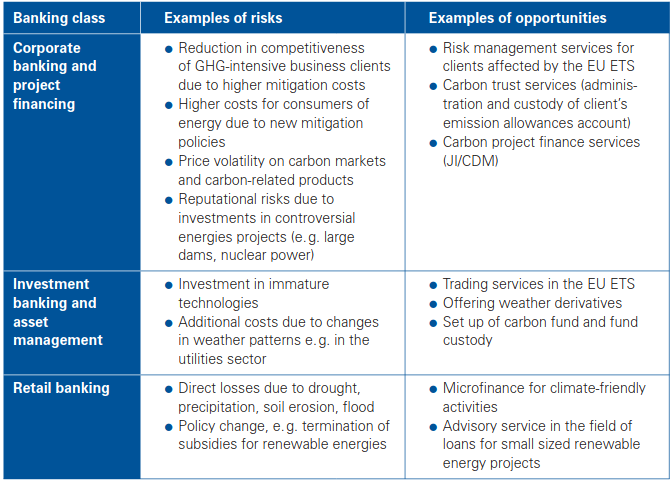

Banks play an important place in the OECD economies and will have a key role to play in the economy as the society transitions to a low-carbon world through financing and investment decisions, credit risk management policies and lending practices, and the development of risk mitigation products. Climate change policies such as the Paris Agreement, EU ETS, and Kyoto Protocol pose new risks and offer new opportunities to banks.

Figure 6: Important Climate-Related Risks and Opportunities for Banks (Courtesy: Dlugolecki and Lafled, 2005)

Credit risk

The biggest risk to banks is from their lending activities. Potential loan losses for the banks resulting from the business interruptions and bankruptcies caused by storms, droughts, wildfires and other extreme events. As governments and regulators enact new policies to limit GHG emissions, new liabilities and therefore business risks, for instance via tradable emission certificates to the economy. These policies will inflict direct costs of compliance on related industries and indirect costs on all consumers of energy and electricity. This, in turn, will affect the credit quality of the high-carbon borrowers and thereby bank risks. These policies will also have implications on banks businesses such as loan origination, equity, fixed income, trade and project finance.

Banks will also have to update their internal risk assessment processes as it relates to climate change. For example, failure in climate due diligence for investments and loans could affect margins. Banks also face operational risks from their client relationships. If, for instance, clients fail at carbon risk management, then that could lead to financial sanctions which could impair the clients’ liquidity and therefore the bank’s competitiveness and creditworthiness. Although large banks are fairly diversified, the risks are more pronounced for smaller, regional rivals who have concentrated clientele such as banks in farmbelt and in energy rich states.

Market risk

A paper by CFTC finds that variables such as economic growth, crop yields, and labor productivity deteriorate more quickly and suddenly once a threshold temp has been crossed (Burke, et al., 2015). If these variables deteriorate non-linearly in response to CC impacts, sudden and disorderly price adjustments in fin mkts become more likely (Hong, et al. 2020). Breakthroughs affecting low-to-zero carbon tech can also lead to discontinuities and consumer preferences and energy consumption patterns can change unexpectedly and rapidly (Kuran & Sunstein, 1998)

Market risks are significant for the banks and their clients from re-pricing of energy commodities such as fossil fuels as a result of decline in demand or change in sentiment toward these energy sources. There are also risks for heavy industries such as steel, aluminum, automobile, shipping, plastics, and chemicals, whose fortunes are tied to that of oil prices. In fact, (Kahn, et al, 2019) found that all 11 sectors of the U.S. economy would be impacted by climate change. This is prompting some industries to evolve their operations to be less energy intensive and use less packaging, for instance.

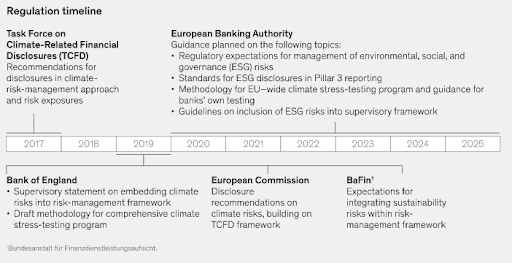

Regulatory risk

(Ezeiza, et al, 2020) say that the banks are coming under the regulatory and commercial scanner to protect themselves from the impact of climate change and to align themselves with the global sustainability agenda. Banking regulators around the world, now formalizing new rules for climate change management, intend to roll out demanding stress tests in the months ahead.

The UK’s Prudential Regulation authority was among the first to set out detailed expectations for governance, processes,and risk management. These require banks to identify, measure, quantify, and monitor exposure to climate risk and ensure that the necessary technology and talent are in place. Germany’s BaFin has followed with similar requirements.

Among the upcoming initiatives, the Bank Of England (BOE) plans to devote its 2021 Biennial Exploratory Scenario (BES) to the financial risks of climate change. The BES imposes requirements that will probably force many financial institutions to ramp up their capabilities, including the collection of data about physical and transition risks, modeling methodologies, risk sizing, understanding challenges to business models, and improvements in risk management. The European Banking Authority or EBA is establishing regulatory and supervisory standards for Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) risks and has published a multi-year sustainable-finance action plan. The EBA may provide a blueprint for authorities in geographies including the US, Canada, and Hong Kong, which is also considering incorporating climate risk into their supervisory regimes. (Ezeiza, et al, 2020).

Figure 7 – Regulation is Evolving at High Speed (courtesy: Ezeiza, et al, 2020)

Legal risk

As communities feel the effect of climate change, litigation seeking to hold corporate actors accountable for climate change impacts and addressing property and constitutional concerns related to these impacts or government adaptation responses will grow in importance.

State attorneys general have brought cases seeking to hold private sector entities accountable for contributing to climate change. Two cases testing the waters of materiality of climate-related information have resulted in opinions to date. A federal district court denied a motion to dismiss in a shareholder suit against ExxonMobil, acknowledging that certain types of information related to climate change transition risks could be material to reasonable investors in the process.

The New York attorney general brought a second case resulting in an opinion. In NY v. ExxonMobil, the court considered whether ExxonMobil misled investors in disclosures about the potential impacts of future climate policies on product demand and how the firm incorporated this information in project-level business planning. Although, the court found the plaintiffs’ experts unpersuasive and no evidence of impact on investors’ analyses or decisions during the relevant timeframe. (Vizcarra 2020) says that “The widespread, deepening interest by shareholders in various types of climate change information suggests that future litigation around the materiality of such information is likely, particularly as climate change impacts become apparent in corporate bottom lines and acute events.”

Climate change impacts and adaptation costs in cities and states threaten property values, tax bases, and municipal bond valuations. In some cases, local governments could face tort claims for flood damage to private property. (Rupert and Grimm, 2013). NY and MA cases also highlight the potentially crippling adaptation and resilience costs faced by local govts in responding to increasing climate change impacts. As cities and states better understand their climate-related risks and begin to fully evaluate potential costs, the costs of mounting even long-short litigation to help defray portions of the costs becomes a more reasonable calculation.

Would banks be caught in the crossfire? It is hard to say at this point if banks can be held liable for the actions of their clients, such as fossil fuel companies for exacerbating climate change via their products and business models. Banks do sizable business with the fossil fuel industry. (Banktrack 2019) (Turnbull and Fitzgibbon, 2020) reckon that between 2016-2019, four years since the Paris Agreement was signed, banks have lent $2.7 trillion to the fossil fuel industry.

Opportunities

Climate change, in addition to creating risks for the banks, also offers new opportunities such as renewable technologies, energy efficiency and storage projects, mobility projects, emission trading and weather markets, and climate change related microfinance.

Emission trading offers new client service opportunities for the banks for market making and flow trading. Ever since European Union Allowances (EUA) were made available in 2005, several banks have entered the market providing liquidity. Emission trading is also an option for project financiers, since the IRR of emission reduction projects can be enhanced through project-based mechanisms like Joint Implementation (JI) and Clean Development Mechanism (CDM). For example, under JI, one industrialized country invests in an emission reduction project in another industrialized country and receives credits for achieved emission reductions – so called Emission Reduction Units (ERUs). Under the CDM, an industrialized country invests in a project in a developing country and receives credits for emission reductions, an arrangement called Certified Emission Reduction Units (CERs).

Weather derivatives help mitigate weather-related risks. Initially, weather derivatives were traded over-the-counter. Since 1999, CME has launched weather futures and weather options on futures. Currently, derivatives are available for nine US cities, two European cities, and one city in Japan.

Structured finance is another opportunity for banks. The range of major facilities needing finance sector support include renewables and low-carbon technologies.

Insurance

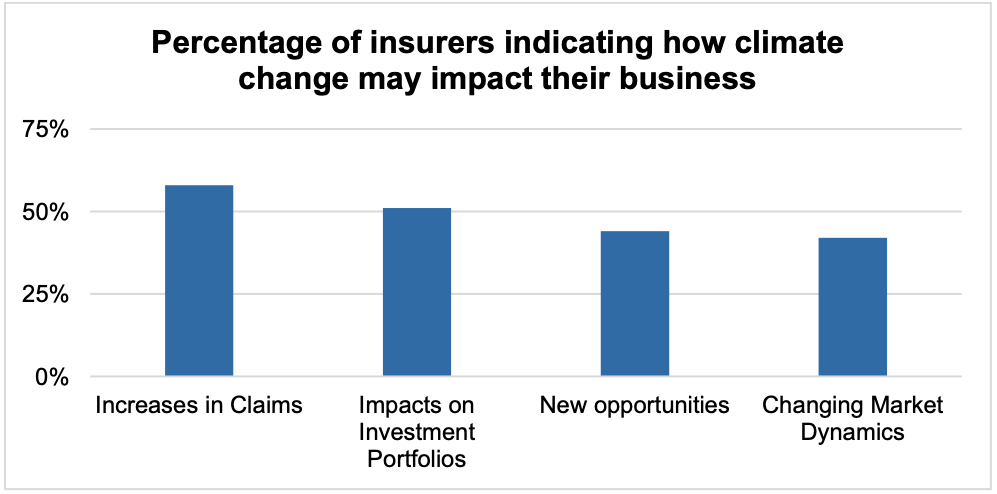

Insurers play a dual role as risk managers protecting society’s assets and long-term investors funding the economy. Climate change and climate policy affect insurers through the risks they accept from clients when they sell protection. Through their investment, underwriting and advisory functions, insurers are directly exposed to a changing climate, which creates threats and opportunities for the sector. (Surminski, 2020) (Waddell and Beal, 2020).

Figure 8 – Expected Impacts of Climate Change on Insurers (Courtesy: Surminski, 2020)

(Bachir, 2020) equates climate risk to insurance risk. (Donlon, 2020) highlights five risks for the insurance companies:

- Regulatory: The government could create mechanisms for carbon pricing, renewable energy mandates, electric vehicle support, and tax subsidies or penalties

- Litigation: Liability risks exist in two ways: insurers facing litigation because of their corporate practices, and litigation impacting their customers. As of 2019, climate change litigation cases have been present in at least twenty-eight countries around the world, with a majority of cases in the United States. (Setzer and Byrnes, 2019) Litigation is increasingly viewed as a policy tool to influence both public and private sector behaviour, but there is a disconnect within the insurance industry surrounding this threat– climate change litigation strategy is not yet embedded in insurer strategy, nor have the risks across jurisdictions and business been assessed to the point of providing input for investment decisions. (Surminski, 2020-2). The evidence of climate change litigation is still at a mostly anecdotal stage, and it is essential that as this evidence continues to develop, research, and analyze climate-related liability risk as the insurance industry continues to develop as well. (Setzer and Byrnes, 2019). The threat is of excessive verdicts, injunctions, and punitive damages (Surminski, 2020).

- Reputational: Brand market value can be severely damaged as BP Oil learned from the Deep Water Horizon disaster, and further exacerbated by social media

- Transitional: Global economic activity will be radically rebalanced in the decarbonization transition. This will have impacts on investment portfolios, particularly in the context of the devaluation of holdings in carbon-intensive industries, and new investment opportunities in the growth of low-carbon technologies as the world moves to a low carbon economy (Surminski, 2020). Insurers face the risk of losses from covering businesses or assets that will not adapt to the new low carbon economy, such as coal mines or other fossil fuel companies. Transition risk is also relevant for the underwriting side of insurance, and some companies have started to limit or exclude carbon-intensive sectors from their insurance portfolios. The rating agency Moody’s reports that, “While thermal coal is a relatively large sector, we do not expect large diversified insurers’ thermal coal exclusionary policies to result in a meaningful loss of business.” (Wilkinson, 2019). In general, potential expected challenges in transition risk arise from uncertainty about future regulations and technologies, and the risk of asset-stranding or sudden shifts in operational practices, risk profiles, and insurance needs of companies and sectors.

(Berglog and Theile, 2019) give an interesting example of the impact that this has on the insurance market in the shipping sector, which conveys percent of world trade. A third of current maritime trade comprises fossil fuels, which will quickly decline. In turn, shipment of biomass, renewable equipment and lithium cargo is expected to rapidly increase, which creates new risks for transporters that will require insurance cover. Additionally, the shipping sector will also have to reduce its own emissions: Current International Maritime Organization (IMO) ambitions require zero-emission vessels by 2030, which encompasses things like the use of lighter materials, greener propulsion devices including wind turbines, and reducing emissions in ship-port interfaces. (Berglog and Theile, 2019). In response, insurers can help facilitate investment in low-carbon technologies by supporting more effective risk-sharing between vessel owners and charterers. In shipping as well as in other sectors, insurers have the opportunity to help manage these risks for their clients and are thus a necessary and important player in the transition to decarbonization.

- Physical: Due to extreme events such as flooding, hurricanes, drought, diminished fresh water supply, or lethal heat waves, damages could create “stranded assets.” For instance, airport runways could remain underwater for days or telecommunication systems could lose power for a sustained length of time.

In 2019, direct economic losses and damage from natural disasters were $232 bn from 409 total natural disaster events. Only a small portion of these are currently insured, creating a large “protection gap”. (Surminski, 2020)

Rising physical risks threaten insurability as well as affordability of existing coverage. Higher claims will require higher premiums, which will jeopardize affordability. The unpredictability of national disaster events creates a situation in which insurance companies suffer from the ‘inability to assess and quantify probabilities of predicted losses with sufficient precision,” meaning that insurers are often reluctant to insure disaster risks without a high premium or cost to the customer. Premiums might indeed be expected to rise on average, as markets continue to fluctuate in response to climate change (Westcott et al, 2020).

Regulators and Supervisory bodies are starting to act. For example, the Bank of England is asking British insurers to assess how global warming might impact the value of stocks and bonds they hold – and its potential to upend financial markets.

What are other risks?

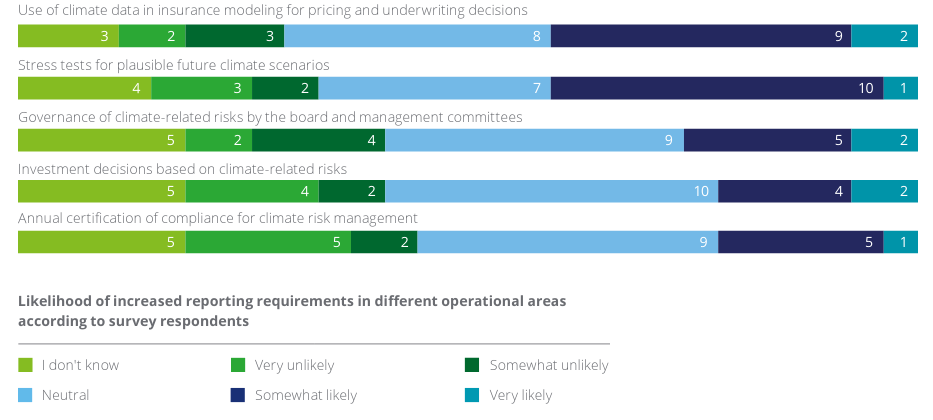

Figure 9 – Reporting Requirements for Insurance Companies Could Increase (Courtesy: Bachir, et al, 2019)

(Bachir, et al, 2019) survey found that

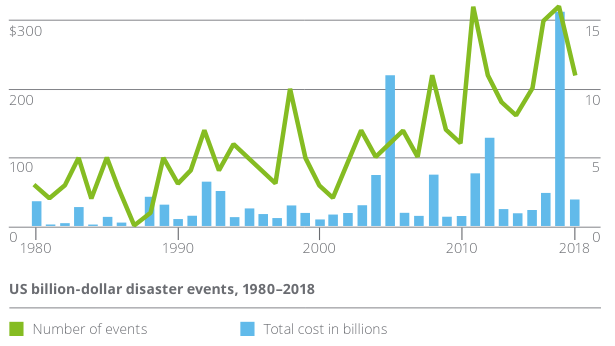

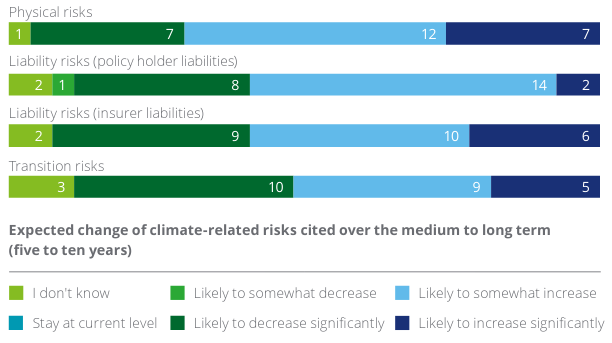

- The regulators are concerned about the solvency of the insurance firms as a result of rising weather-related losses (Figures 10 and 11). The majority of the regulators, however, were either unaware or not fully convinced about how prepared insurers are to deal with climate-related risks.

- While severe weather-related losses could stress insurers’ financials and stoke stability concerns (something that CFTC report also highlights), rising premiums and reduced coverage in response to climate-related risks may undermine the availability and affordability of coverage.

- Balancing solvency concerns with consumer needs will likely be a major challenge when it comes to covering climate-related exposures, likely requiring more information on the costs and perils for carriers and regulators alike.

Figure 10 – Rising Weather Related Losses (Courtesy: Bachir, et al, 2019)

Figure 11 – Insurance Regulators Expect Climate-Related Risks to Increase over Medium- to Long-term (Courtesy: Bachir, et al, 2019)

(Golnaraghi, 2018) points to several challenges in insurers’ ability to successfully deal with climate-related risk transfer, for instance, “limited access to risk information and lack of incentives for customers to take up insurance as a result of post-disaster government relief. Moreover, the scaling-up of investments by insurance firms in green assets and critical infrastructure is inhibited by the lack of well-defined asset classifications, the capacity allocation of relevant markets, as well as fragmented climate policy and regulatory frameworks.”

Since climate scientists predict an increase in the frequency and intensity of climate events such as storms, floods, and wildfires, and because of the resulting risk of catastrophic property claims, insurers are likely to regard climate change as a threat rather than an opportunity.

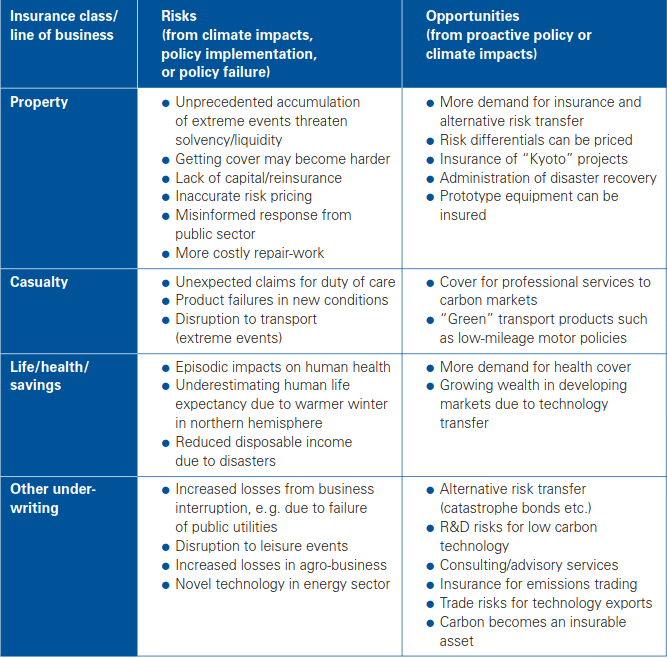

Insurers need to adapt to climate change by assessing how changing weather patterns will influence their clients’ exposure. They must adapt their risk assessment and review their underwriting (pricing, contract conditions and risk acceptance procedures) with a view to their specific risk exposure (line of business, geography etc.), business opportunities, and the type of customer (private, commercial, industrial) they are focused on (Figure 12).

Figure 12: Climate-Change Related Risks and Opportunities for Insurers (Courtesy: Dlugolecki and Lafeld, 2005)

Opportunities

A Boston Consulting Group (BCG) survey cited in (Waddell and Beal, 2020) of 3,000 people in eight countries, found that 70% of the people are now more aware (than pre-COVID-19) that human activity threatens the climate. Furthermore, 87% of respondents said that firms should integrate ESG concerns into their product, services, and operations to a greater extent than they have in the past. Insurers have come to realize that climate change has significant, direct impacts on their industry. (Waddell and Beal, 2020) say that

- A coherent climate strategy can bolster the underwriting business, such as by spurring the development of new types of insurance and targeting new customers. (IFC, 2016) reckons that global electricity demand will grow by 30% in the next 10 years (by 2030), prompting $23 trillion in renewable energy in emerging markets in that period. The new businesses and assets in those markets represent a sizable and growing underwriting market for insurers

- There is increasing evidence that insurers that factor in climate and other ESG issues into decision making are likely to improve their investment performance.

- Insurers that take a leading role on climate, integrating climate risk into their investment processes, will be more competitive in winning third-party investment mandates, especially from institutional investors, such as pension funds.

- Insurers with ambitious climate strategies and transparent disclosure will likely burnish their brands and improve their ability to attract and retain talent.

Conclusions

The potential disruption and financial implications of climate change are imminent as (Colas et al., 2019) point out. If PG&E is the “first climate-change bankruptcy,” it will certainly not be the last. As the impact of climate change prompts high financial stakes and substantial structural adjustments to the global economy, banks will face both climate risks and opportunities. In this context, banks need to treat climate risk as a financial risk, not just a reputational one, and integrate climate considerations into their financial risk management frameworks. The management of climate risk is a new exercise and will continue to evolve.

Insurers also have an opportunity to bridge the knowledge gap about climate change risk across both the underwriting and asset sides of their industry and work towards ensuring exposure to climate risks are embedded into investment decisions. After a disaster or climate shock hits, insurers are an essential player to make sure infrastructure is rebuilt in a low-carbon and climate-resilient way. (Surminski, 2020).

(Boston Common, 2019) Impact Report finds several areas of incremental progress on sustainability within the banking sector in the previous 18 months – there is broader adoption of TCFD guidance, new risk assessment and scenario tools, and more banks are carrying out risk assessments and scenario analyses. (Boston Common, 2020) study states that in 2019, 67% of banks have adopted a group-wide climate strategy, up from 58% from 2018. And, 81% are now disclosing information on progressive climate-related public policy engagement (up from 71% in 2018). But these are not translating into good commercial behavior. Green financing commitments still lag investments in the fossil fuel industry or industries responsible for deforestation.

Fossil fuel producers and high-carbon users will become worse credit risks as their business models become obsolete; so lending to them embeds worsening credit risk into bank balance sheets, setting up for high levels of non-performing assets and defaults. Similarly, changing consumer preference and push back as well as climate change itself will lead to deforestation-dependent businesses to lose out. Not factoring these risks into financing decisions is short-sighted. (Boston Common, 2019).

As the financial services industry adopts sound, analytical approaches for understanding climate risk, we believe it will become a significant governance and risk management topic. Investors will respond in kind, as the information created by climate disclosures drives their own capital allocations. A richer data environment can fuel more efficient capital markets. Through all these changes, increasing awareness of climate risk within the financial services industry will ultimately generate broad-based benefits for other industries and society as a whole. (Colas et al., 2019).

Authors

Ashutosh Singh is quantitative finance researcher whose interests include financial machine learning and factor models. He is also interested in understanding the impact of climate change on industries. He has a MBA from the Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, MS in Computer Science from the Courant School of Mathematical Sciences, New York University, MFE from the World Quant University, BE(Hons) in Electrical Engineering from Birla Institute of Technology and Science, Pilani, India. He is a CFA Charterholder and a member of Chicago Quantitative Alliance.

Jaishree Singh is an ESG Researcher with a focus on healthcare and food/nutrition products. She received a Master’s degree from Johns Hopkins School of Public Health with a focus on sustainability and nutrition. She helped develop health investment strategies for the Rockefeller Foundation in international markets (e.g. Africa, Asia). She spent two years conducting market research at Boundless for 65+ private investors doing impact investing in healthcare and climate change. She’s currently a Researcher for the Sustainability Investment Leadership Council (SILC-NY), whose aim is to disseminate research on impact investing and better sustainability reporting.

References

- Adrian, T., Covitz, D., & Liang, N. (2014). Financial Stability Monitoring. Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, No. 601. New York, NY.: Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Return to text

- Agrawal, Srijan and Joseph Guiyab (2020), “Greening the Financial System – Practical Insights on Developing a Climate Risk Management Strategy”, RBC Capital Markets. Return to text

- Bachir, Michelle, Nikhil Gokhale, and Prachi Ashani (2020). “Climate risk: Regulators sharpen their focus”. Deloitte Center for Financial Service. Return to text

- Bankrate (2019), “Banking for Climate Finance – Fossil Fuel Finance Report Card 2019”. Return to text

- Bapna, Manish, Carter Brandon, Christina Chan, Anand Patwardhan, Barney Dickson (2019). “4 Things to Know About the Global Adaptation Challenge”. The World Resources Institute. Return to text

- Berglof, Erik and Torsten Thiele (2019). “From ‘Green’ to ‘Blue’ Finance: Integrating the Ocean into the Global Climate Architecture”. LSE Global Policy Lab. London School of Economics. Return to text

- Boston Common (2019). “Banking on a Low-Carbon Future: Finance in a Time of Climate Crisis”. Impact Report 2019. Boston Common. Return to text

- Boston Common (2020). “Advocating for a More Sustainable, Equitable, and Transparent World”. Fourth Annual Impact Report. Boston Common. Return to text

- Burke, M., Hsiang, S. M., & Miguel, E. (2015). “Global non-linear effect of temperature on economic production”. Nature, 527, 235-339. doi:10.1038/nature15725. Return to text

- CFTC (2020), “Managing Climate Risk in the U.S. Financial System”, Report of the Climate-related Market Risk Subcommittee, Market Risk Advisory Committee of the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission. Return to text

- Colas, John T., Ilya Khaykin, and Alban Pyanet (2019). “Climate Change: Managing a New Financial Risk”. Oliver Wyman Insights. Return to text

- Dlugolecki, Dr. Andrew and Dr. Shasha Lafled (2005), “Climate Change & the FInancial Sector: An Agenda for Action”. Backrate.org. Return to text

- Donlan, Rosalie (2020). “Insurance industry can find economic opportunity in climate change”. Instant Insights: The Business of Insurance. Return to text

- Eceiza, Joseba , Holger Harreis, Daniel Härtl, and Simona Viscardi (2020), “Banking imperatives for managing climate risk”, McKinsey & Company. Return to text

- Golnaraghi, Maryam (2018). “Climate Change and the Insurance Industry: Taking Action as Risk Managers and Investors”. The Geneva Association. Return to text

- Hong, H., Karolyi, G. A., & Scheinkman, J. A. (2020). “Climate finance”. The Review of Financial Studies, 33(3), 1011-1023. Return to text

- IFC (2016). “Climate Investment Opportunities in Emerging Markets – An IFC Analysis”. International Finance Corporation (IFC). World Bank Group. Return to text

- IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on ClimateChange) (2001),“Climate Change 2001: Third Assess-ment Report: Reports of Working Groups 1 (The Scientific Basis), 2 (Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability) and, 3 (Mitigation)”, Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- IPCC (2014), “Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change” [Field, C.B., V.R.

- Barros, D.J. Dokken, K.J. Mach, M.D. Mastrandrea, T.E. Bilir, M. Chatterjee, K.L. Ebi, Y.O. Estrada, R.C. Genova, B. Girma, E.S. Kissel, A.N. Levy, S. MacCracken, P.R. Mastrandrea, and L.L. White (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 1-32.

- IPCC (2019). “Global Warming of 1.5 degree Centigrade: An IPCC Special Report”. Return to text

- Jorgenson, Andrew K., Shirley Fiske, Klaus Hubacek, Jia Li, Tom McGovern, Torben Rick, Juliet B. Schor, William Solecki, Richard York, Ariela Zycherman (2018), “Social science perspectives on drivers of and responses to global climate change”, Wiley Online Library. Return to text.

- Kahn, Matthew, E, Kamiar Mohaddes, Ryan N. C. Ng, M. Hashem Pesaran, Mehdi Raissi and Jui-Chung Yang (2019). “Long-Term Macroeconomic Effects of Climate Change: A Cross-Country Analysis”. Globalization Institute Working Paper 365. Return to text

- Landon-Lane, J., Rockoff, H., & Steckel, R. H. (2011). Droughts, Floods and Financial Distress in the United States. The Economics of Climate Change: Adaptations Past and Present, 73–98. Cambridge, MA.: National Bureau of Economic Research. Return to text

- Mendelsohn.R, Schlesinger.M and Williams.L (2000). “Comparing Impacts Across Climate Models” Integrated Assessment 1, pp. 37-48

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) (2020). “Weather Disasters and Costs”. Return to text

- Setzer, Joana and Rebecca Byrnes (2019). “Global trends in climate change litigation”. London School of Economics. Return to text

- Steele, Paul and Joachim Faber (2005). Foreword to “Climate Change & the Financial Sector: An Agenda for Action”. Backrate.org. Return to text

- Stern.N (2006). “Stern Review on The Economics of Climate Change (pre-publication edition). Executive Summary”, HM Treasury, London. Archived from the original on 31 January 2010

- Stern.N (2006), “Stern Review on The Economics of Climate Change, PART II: The Impacts of Climate Change on Growth and Development”. HM Treasury, London. Archived from the original on 31 January 2010

- Surminski, Swenja (2020). “Climate Change and The Insurance Industry: managing Risk in a Risky Time”. Georgetown Journal of International Affairs. Return to text

- Surminski, Swenja (2020-2). “4+ ways insurance can support a transition to a low-carbon resilient future”. Return to text

- Turnbull, David and Blair Fitzgibbon (2020). “New Report Reveals Global Banks Funneled $2.7 Trillion into Fossil Fuels Since Paris Agreement”. Oil Change International. Return to text

- U.N. Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI)(2017). Drought Stress Testing: Making Financial Institutions More Resilient to Environmental Risks. Frankfurt, GR.: U.N. Environment Programme. Return to text

- Vizcarra, Hana V, (2020), “Regulatory Activity and Legal Liabilities Affecting Management of Financial Climate Risks”, Harvard Law School, Environmental & Energy Program. Return to text

- Waddell, Rebecca and Douglas Beal (2020). ”Insurers Take Up the Climate Fight”. Boston Consulting Group Publication 2020. Return to text

- Wade, Keith and Marcus Jennings. “The impact of climate change on the global economy”. Schroders. Return to text

- Wilkinson, Claire (2019), “No ‘meaningful’ losses for insurers excluding coal risks: Moody’s”. Business Insurance. Return to text