Making Sustainable Investing Sustainable

By Jaishree Singh, Ashutosh Singh

“Everybody complains about the weather, but nobody does anything about it.” A quip by Charles Dudley Warner, a contemporary of Mark Twain perhaps captures the (lack thereof) action on the environmental crisis. The extreme weather events, rising sea levels, more frequent and stronger storms are further exacerbating the social, economic and environmental stress on the most vulnerable communities of the world. So, what can be done to turn around this situation? IMG Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva (Georgieva, 2019) highlights, “… dealing with climate change requires not only mitigating damage, but also adapting for the future. This means pricing risk, and providing incentive for green investment”. (Koller et al 2020 and Olesinski et al, EY Poland) point to a more pervasive issue of “short-termism” and (Collie, 2019)’s “universal ownership”. These will enable sustainable investing which then would help alleviate the stresses caused by climate change.

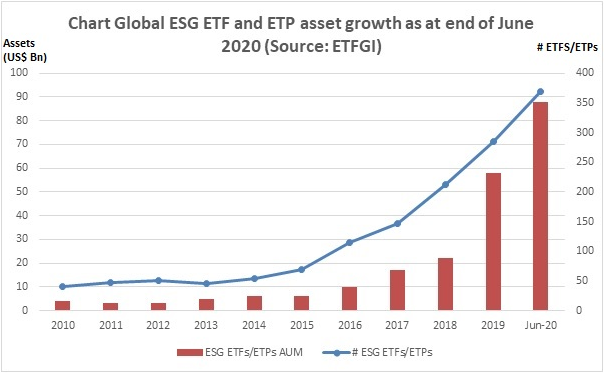

Blackrock defines sustainable investing (Hildebrand et al, 2020) as “[c]ombining traditional investing with environmental, social, and governance-related (ESG) insights to improve long-term outcomes …” “ESG-based investing,” where a fund manager uses environmental, social, and governance scores along with financial metrics to make investment decisions, has been gaining prominence since the start of 2010s and has accelerated as more evidence of climate change and the results of social inequities pile up (Figure 1).

Figure 1: EGS Assets and Providers (courtesy of DailyAlts)

Research by J.P. Morgan (Chaudhry et al, 2016), (Clark et al, 2015), University of Oxford, Arabesque Partners, and Callan Investments (West, 2016) find that companies that are in the top bracket of ESG scores carry less risk and can generate better long-term performance than their peers in the same industry. Sustainable investing, therefore, is not only good for the environment and society but also makes business sense.

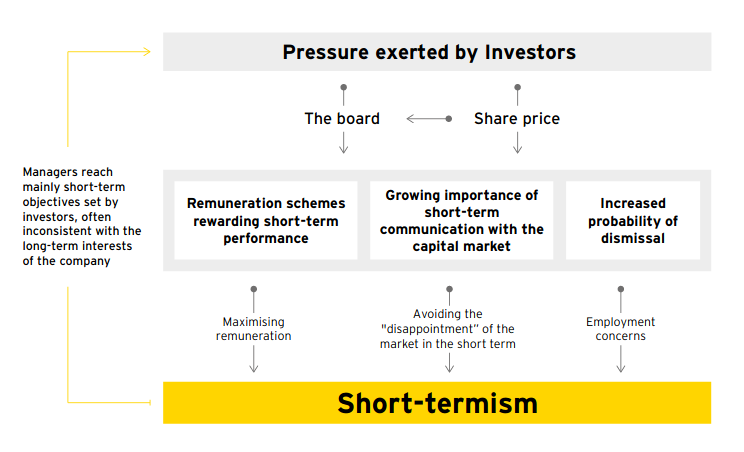

However, in order for sustainable investing to become fully integrated into mainstream, the investment community will need to change habits (like short-termism – Figure 2 (Olesinski et al, EY Poland) and adopt new ones (such as ‘Universal Ownership’ (UNEP Finance Initiative), and managers will need to generate market returns.

Figure 2: Short-termism (courtesy of EY Poland)

In this note, we discuss actions taken by various agents in the investment chain – asset owners, asset managers, and individual firms (investee companies) to make sustainable investing sustainable.

Case for Sustainable Investing (SI)

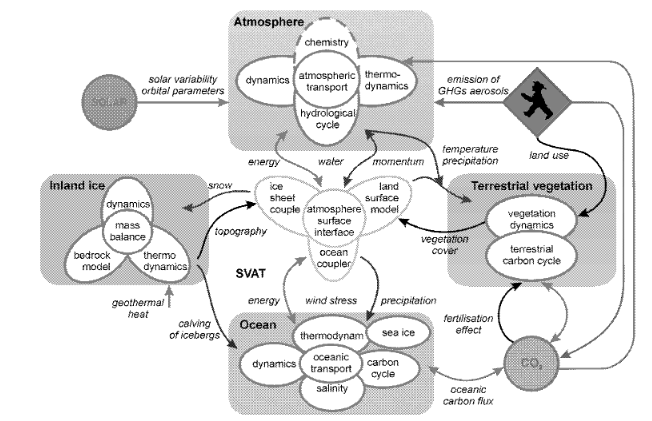

Sustainable investing addresses the underlying issues of climate change and social inequality. (Deng et al, 2019) have shown that the effect of climate change is non-linear because of negative externalities. The seriousness of the crisis was highlighted in the 2018 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, which said that to limit warming to 1.5 deg centigrade would require that humans decrease emissions by 45% by 2030 and net-zero by 2050. Climate change is intricately linked to social inequality as (S.Nazrul Islam and John Winkel, 2017) show in their paper. Their research finds that “disadvantaged groups suffer disproportionately from the adverse effects of climate change” and that leads to even greater inequality. (OECD, 2003) Poverty and Climate Change and the (US. Global Leadership Coalition 2020) report highlights how climate change exacerbates social, health, and economic stresses on already fragile communities, particularly youth and children.

(IEA, 2017) reckons that to meet climate goals, “a deep transformation of energy production and consumption needs to occur by 2050.” Changes will cost on average $3.5 trillion/year every year until 2050 as per the (IEA, 2019). Mark Carney, former governor of the Bank Of England, in (Carney, 2019) says that this will require a ‘sustainable finance system’ – “funding the initiatives and innovations of the private sector and amplifying the effectiveness of the governments’ climate policies.” To facilitate that, sustainable investing must go mainstream along with comprehensive climate disclosure, and transformed climate risk management.

Figure 3: The Feedback Loops (courtesy of Rial J. A. et al.)

Sustainable investing creates incentives for capital owners to provide desired investment outcomes while also solving global climate and societal needs. That is already happening to some extent. (Morgan Stanley, 2020) in a 2019 bi-annual survey of 110 asset owners (AOs) found that 80% integrated sustainable investing in their asset allocation decisions, up 10 points from a similar survey in 2017. The survey found that allocators see higher return potential as the key driver behind allocating exclusively to managers that have formalized “sustainability approaches” in the future. Gov. Mark Carney (Carney, 2019) says that, “financial markets recognize sustainable investment as a new horizon that opens up enormous opportunities ranging from transforming energy to reinventing protein.” Investors are increasingly considering the environmental impact of their investments alongside pure financial gain.

The Playbook

ESG scores provide a quantitative foundation for investing in the long run. (Chaudhry et al, 2016) of J.P. Morgan define them as follows:

Environmental scores evaluate “the way a company uses its [physical] resources and sets policies to limit its environmental impact and protect the environment.” This includes carbon emissions, pollution, and critical resource utilization such as water or mineral-rich soil.

Social scores evaluate a company’s policy “toward employees, suppliers, customers, and communities.” This includes employment and pay equality, health and safety standards, employee satisfaction, and labor/community relations. An example of positive correlation between high employee satisfaction and stock price is a study by (Admans, 2012). It showed that firms with high employee satisfaction outperform their peers by 2.3%-3.8% per year.

Governance scores evaluate a company’s “corporate policies and procedures, demographic and gender diversity in functional teams, executive compensation, business ethics and diversity of board.” (Daniels et al, 2019) found a positive correlation between press announcements of companies’ gender diversity achievements and a rise in stock prices for those companies. (Barsade et al 2000) and (Dobbin and Jung, 2011) also found that teams with functional diversity solve problems faster and more effectively .

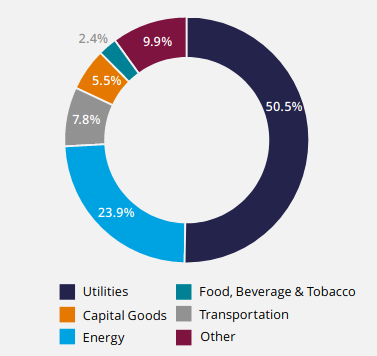

In this note, we focus on sustainable investing from an environmental and climate perspective mainly because it is a large (CDP, 2019) shared problem that will affect everyone globally and its effects will grow non-linearly if left unattended. For example, a group of global firms with a market capitalization of $17 trillion (as of June 30, 2019) expect to be hit by $1 trillion in losses within the next five years.

Figure 4: Scope 1 & 2 Emissions (courtesy of AberdeenStandard)

Scope 1 – direct emissions. Scope 2 – Indirect emissions from purchased energy for electricity, heat etc.

We next discuss how asset owners, asset managers, and companies are changing their behavior as they reckon with the challenges of long-term investing and generating sustainable returns. These changes are partially driven by demands of stakeholders that are upstream from an investment link. For instance, asset owners are accountable to people whose assets they manage (e.g. high net-worth individuals), asset managers are accountable to asset owners and so on.

Asset Owners (AOs)

Traditionally, institutional investors such as pension funds, endowments and foundations, and insurance companies are called asset owners. These include:

- Japan’s Government Pension Investment Fund (GPIF) AUM $1.5 trillion

- Norway’s Government Pension Fund Global managed by the Norges Bank (GPFG) AUM $1.03 trillion

- Calpers or California Public Employee Retirement System AUM $400 billion, and

- OMERS or Ontario Municipal Employment Retirement System AUM $84 billion

Many of these AOs have both in-house and external portfolio managers. (Hawley and Williams, 2000) said that asset owners invest for a long term and their portfolios are well-diversified. As a result, they own “a slice of the whole economy” or have exposure to the entire market rather than individual assets. In other words, they are “universal owners (Collie, 2019).” It is therefore in their interest to maximize positive “externalities” (beneficial societal impact) and minimize negative ones by looking at the “total picture.” Additionally, AOs are now asking asset managers to integrate ESG factors alongside financial analysis in their asset allocation (Mackenzie, 2019) and portfolio construction (Bruder et al, 2019) processes, and make them accountable for non-concessionary (Brest and Born, 2013) returns.

Furthermore, they are investing in managers for the long-term so that they, in turn, can invest in portfolio companies for a longer period. A joint National Investor Relations Institute and Stanford University study (Beyer et al, 2014) found that “firms with long-term shareholders are able to implement corporate strategy and allocate capital to long-term investments without distraction and focus on short-term performance.”

Asset Managers (AMs)

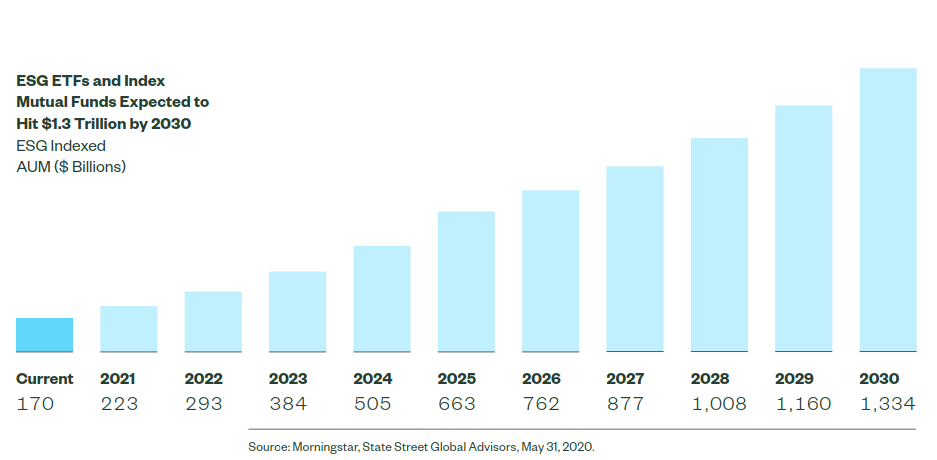

A July 2020 report (Tobin et al, 2020) says that ESG ETFs and Index mutual funds will go from $170 billion today to $1.3 trillion in ten years. Morningstar’s research found that “72% of the Morningstar’s equity indices that incorporated ESG screens lost less than the market during down periods for the last five years through the end of 2019. And, 89% of the 57 ESG-screened indices beat the broad market equivalents in Q1/2020.” MSCI (Nagy and Giese, 2020) also finds that ESG indices out-performed their parent indices. This is powerful evidence that is driving asset managers to incorporate ESG in their investment process along with traditional financial analysis. We reckon that AMs will continue to look for firms that have either good ESG scores or are likely to improve them (ESG momentum). KPMG (Cowell and Rajan, 2020) believes that in the future, AMs and hedge funds will seek cooperation with AOs in the form of longer investment periods so that they can work with investees to improve their policies, processes, and products from an ESG lens.

Figure 5: ESG ETF Growth (courtesy of ESG Investing)

Companies

Companies generally seek long-term finance so that they can better execute corporate strategies and invest in projects/assets that have higher returns but are long duration. A World Bank study (Bruhn, 2015) cites evidence that long-term finance has a positive effect on a company’s investment performance. The study also finds that quarterly reporting and overemphasis on stock price puts undue pressure on management to not undertake projects that will ultimately generate higher long-term sustainable returns and benefit employees, customers, and the community.

There are some changes that are less controversial, such as: a diverse board, equality in hiring decisions, product design that uses less material and packaging etc. These types of changes have generally led to higher sales (Lorenzo et al, 2018) and greater profitability (Orlitzky, M. et al, 2003). That, in turn, may lead to diverse and committed customers, employees, and shareholders. All these bring down the cost of capital, which then has a “flywheel effect” of more investment in higher return (but long-term) projects. As a second order effect, it forces competition to adopt better practices because investors demand greater risk premiums from non-compliant firms.

In Conclusion

ESG investing had been gaining traction for the last decade as the world began to experience the effects of climate change and the downsides of unfettered capitalism. The debate on the merits of capitalism aims to find the balance between its ‘winner takes all’ mindset, and its unintended consequence of placing disadvantaged people in more vulnerable positions.

The COVID-19 crisis, which adversely affects poor and minorities the hardest, has thrust all elements of ESG to the forefront and we see increasing support for sustainable investing policies and actions even among skeptics (Tolbert, 2019).

The central thesis of this note is that for sustainable investing to thrive and become sustainable itself in the long-term, the key links in the investment chain – AOs, AMs and companies will have to:

- Move away from short-termism (Olesinski et al, EY Poland)

- AOs need to think of themselves as ‘Universal owners,’ and

- Sustainable funds need to generate ‘market returns’

To facilitate this, ESG rating providers will need to agree to consistent* and robust standards around the definitions, terminology, and data underlying ESG factors just like credit ratings. Second, the investment management industry wants consistent and coordinated policy action across national boundaries. This would help execute deals and reduce operating costs.

*We reckon that sustainability reporting frameworks like SASB and TCFD along with regulation could catalyze this

Authors

Jaishree Singh is an ESG Researcher with a focus on healthcare and food/nutrition products. She received a Master’s degree from Johns Hopkins School of Public Health with a focus on sustainability and nutrition. She helped develop health investment strategies for the Rockefeller Foundation in international markets (e.g. Africa, Asia). She spent two years conducting market research at Boundless for 65+ private investors doing impact investing in healthcare and climate change. She’s currently a Researcher for the Sustainability Investment Leadership Council (SILC-NY), whose aim is to disseminate research on impact investing and better sustainability reporting.

Ashutosh Singh is quantitative finance researcher whose interests include financial machine learning and factor models. He is also interested in understanding the impact of climate change on industries. He has a MBA from the Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, MS in Computer Science from the Courant School of Mathematical Sciences, New York University, MFE from the World Quant University, BE(Hons) in Electrical Engineering from Birla Institute of Technology and Science, Pilani, India. He is a CFA Charterholder and a member of Chicago Quantitative Alliance.

References

Alternative Investments, ESG and Sustainability News. (July 23, 2020) “ESG Funds More Than Triple in Latest Year”. Available at: https://dailyalts.com/alternative-investments-inflows-into-esg-etfs-in-the-first-half-of-2020-more-than-tripled-from-last-year/

Barsade, Sigal G., Andrew J. Ward, Jean D. F. Turner, and Jeffrey A. Sonnenfeld. (2000) “To Your Heart’s Content: A Model of Affective Diversity in Top Management Teams”, Administrative Science Quarterly 45, no. 4 (December 2000): 802–36. doi:10.2307/2667020.

Beyer, Anne, David L. Larcker, and Brian Tayan. (2014) “2014 Study on How Investment Horizon and Expectations of Shareholder Base Impact Corporate Decision-Making.” Available at: https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/publication-pdf/cgri-survey-2014-investment-horizon.pdf

Brest, Paul and Kelly Born. (2013) “Unpacking the Impact in Impact Investing”, Stanford Social Innovation Review. Available at: https://ssir.org/articles/entry/unpacking_the_impact_in_impact_investing

Bruder, Benjamin and Cheikh, Yazid and Deixonne, Florent and Zheng, Ban, Integration of ESG in Asset Allocation. (October 25, 2019). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3473874 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3473874

Bruhn, Miriam. (2015) “Firms’ use of long-term finance: why, how, and what to do about it?” World Bank Blogs. https://blogs.worldbank.org/allaboutfinance/firms-use-long-term-finance-why-how-and-what-do-about-it

Carney, Mark. (12/2019, page 12) “50 Shades of Green”, Finance & Development, December 2019, Vol. 56, No. 4. Available at: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2019/12/index.htm

CDP. (2019) “World’s biggest companies face $1 trillion in climate change risks”. Available at: https://www.cdp.net/en/articles/media/worlds-biggest-companies-face-1-trillion-in-climate-change-risks

Chaudhry, Khuram, V. Shaikh, A. Hanif, D. Lakos-Bujas, R. Smith, B. Hlavaty, and M. Kolanovic. (2016) “ESG – Environmental, Social & Governance Investing”, J.P. Morgan. Equity Quantitative Strategy. Available at: https://yoursri.com/media-new/download/jpm-esg-how-esg-can-enhance-your-portfolio.pdf/view

Clark, Gordon L., Andreas Feiner, Michael Viehs. (2015) “From the Stockholder to the Stakeholder”. Available at: https://arabesque.com/research/From_the_stockholder_to_the_stakeholder_web.pdf

Collie, Bob. (2019) “Commentary: Universal ownership – the world’s largest asset owners look differently at investing”. Pension & Investments. Available at: https://www.pionline.com/article/20190430/ONLINE/190439999/commentary-universal-ownership-the-world-s-largest-asset-owners-look-differently-at-investing

Cowell, Anthony and Amin Rajan. (2020) “Sustainable Investing: fast-forwarding its evolution” KPMG, Create-Research, AIMA and CAIA Report. https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/xx/pdf/2020/02/sustainable-investing.pdf

Daniels, David P, Jennifer E. Dannals,Thomas Z. Lys and Margaret A. Neale. (2019) “Yes, Investors Care About Gender Diversity”. Available at: https://insight.kellogg.northwestern.edu/article/women-in-tech-finance-gender-diversity-investors

Deng, Jiechun, Aiguo Dai, and Haiming Xu. (2019) “Nonlinear Climate Responses to Increasing CO2 and Anthropogenic Aerosols Simulated by CESM1”, Journal of Climate (2020) 33 (1): 281–301. Available at: https://journals.ametsoc.org/jcli/article/33/1/281/346163/Nonlinear-Climate-Responses-to-Increasing-CO2-and

Dobbin, Frank and Jiwook Jung F.Dobbin. (2011) “Corporate Board Gender Diversity and Stock Performance: The Competence Gap or Institutional Investor Bias?”. North Carolina Law Review 89 (3):809-838. Available at: https://ddi.law.unc.edu/documents/boarddiversity/dobbin.pdf

Edmans, Alex. (2012) “The Link Between Job Satisfaction and Firm Value,With Implications for CorporateSocial Responsibility”. Academy of Management Perspectives Vol. 26, No. 4. Available at: http://faculty.london.edu/aedmans/RoweAMP.pdf

Georgieva, Kristalina. (12/2019, page 20) “The Adaptive Age”, Finance & Development, December 2019, Vol. 56, No. 4. Available at: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2019/12/index.htm

Hawley, James, and Andrew Williams. “The Emergence of Universal Owners: Some Implications of Institutional Equity Ownership.” Challenge, vol. 43, no. 4, 2000, pp. 43–61. Available at: JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40722019.

Hildebrand, Philip, Rich Krushel, Andre Bertolotti, Brian Deese, and Carolyn Weinberg. (2020) “Sustainable Investing: resilience amid uncertainty.” Blackrock 2020: https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/literature/investor-education/sustainable-investing-resilience.pdf

IEA. (2017) “Deep energy transformation needed by 2050 to limit rise in global temperature”, IEA, Paris. Available at: https://www.iea.org/reports/the-critical-role-of-buildings

IEA. (2019) “The Critical Role of Buildings”, IEA, Paris. Available at: https://www.iea.org/reports/the-critical-role-of-buildings

Koller, T, Goedhart M., & Wessels, D. (2020) Valuation: measuring and managing the value of companies. Hoboken, N.J., John Wiley & Sons.

Lorenzo, Rocio, Nicole Voigt, Miki Tsusaka, Matt Krentz, and Katie Abouzahr. (2018) “How diverse leadership boosts innovation.”. BCG. https://www.bcg.com/en-us/publications/2018/how-diverse-leadership-teams-boost-innovation

Mackenzie, Craig. (2019) “Strategic Asset Allocation: ESG’s new frontier”. Aberdeen Standard Investments. Available at: https://www.aberdeenstandard.com/docs?editionId=831104c8-8228-49fd-82f5-7c6a39e07727

Morgan Stanley. (2020) “Sustainable Signals: Asset owners see sustainability as core to the future of investing”. Available at: https://www.morganstanley.com/content/dam/msdotcom/sustainability/20-05-22_3094389%20Sustainable%20Signals%20Asset%20Owners_FINAL.pdf

Nagy, Zoltan and Guido Giese. (2020) “ MSCI ESG Indices during the coronavirus crisis”. https://www.msci.com/www/blog-posts/msci-esg-indexes-during-the/01781235361

OECD. (2003) “Poverty and climate change: Reducing the Vulnerability of the Poor through Adaptation”. OECD. Available at: (Part 1) https://www.oecd.org/env/cc/2502872.pdf

Olesinski, Bartosz, Pawel Opala, Marek Rozkrut, and Andrzej Toroj. “Short-termism in business”, EY Poland. https://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/EY_Poland_Report/%24FILE/Short-termism_raport_EY.pdf

Orlitzky, M., Schmidt, F. L., & Rynes, S. L. (2003) “Corporate Social and Financial Performance: A Meta-Analysis”. Organization Studies, 24(3), 403–441. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840603024003910

Rial, Jose, Roger Pielke Sr., M. Beniston, M. Clausssen, J. Canadell, P. Cox, H. Held, N.D. Noblet-Ducoudre, R. Prinn, J. Reynolds, and J. Salas. (2004) “Nonlinearities, Feedbacks and Critical thresholds within the earth’s climate system”. Available at: https://www.globalcarbonproject.org/global/pdf/pep/Rial2004.NonlinearitiesCC.pdf

Nazrul Islam & John Winkel. (2017) “Climate Change and Social Inequality,” Working Papers 152, United Nations, Department of Economics and Social Affairs. Available at: https://www.un.org/esa/desa/papers/2017/wp152_2017.pdf

Tobin, R, S. Thompson, M. Andreetto, M. Victor, M. Arone, S. Smetana, and B. Williams. (2020)

“ESG Investing: From Tipping Point to Turning Point”. State Street Global Advisors. https://www.ssga.com/library-content/pdfs/etf/spdr-esg-investing-tipping-point-to-turning-point.pdf

Tolbert, Jim. (12/30/2019) “Republicans came to the table on climate this year.” The Hill. https://thehill.com/blogs/congress-blog/energy-environment/476210-republicans-came-to-the-table-on-climate-this-year

UNEP Finance Initiative. “Universal Ownership: Why environmental externalities matter to institutional investors”. Available at: https://www.unepfi.org/fileadmin/documents/universal_ownership_full.pdf

U.S. Global Leadership Coalition. (2020) “Climate Change and the Developing World: A Disproportionate Impact”. Available at: https://www.usglc.org/media/2020/03/USGLC-Fact-Sheet-Climate-Change.pdf

West, Anna S. (2016) “2016 ESG Interest and Implementation Survey”. Callan Research. Available at: https://www.callan.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/CallanESGSurvey2016.pdf